Ãëàâíàÿ

Îá ýòîì ñàéòå

Íåìíîãî î ñåáå

Ñòèõè

Êíèãè

Îäíà ïüåñà

Ñêàçî÷íûé àíãëèéñêèé

Âûñòóïëåíèÿ

Èíòåðâüþ

Äëÿ ãàçåò1990 A story about storytelling

1991 Over here

1991 How to tell tall stories

1991 Empty shelves and English

1992 Storytelling in practice

1996 "- Çàêðîéòå çà ìíîé ðîò!"

1997 "- Âû îáîçâàëè ìåíÿ ïîýòåññîé?"

1998 "-ß âñåõ ëþáëþ, è ìíå âñåõ î÷åíü æàëêî"

1999 Î Ðåíàòå, Ìóõàðìñå è ïëàòêå õîáîòîâîì

2004 Ðåíàòà Ìóõà: íà÷àëî ñëåäóåò..

2005 Ïòè÷üè ïðàâà: ïðûãíóòü ñ ïàðàøþòîì ââåðõ...

Íà òåëåâèäåíèè

Íà ðàäèî

×òî áûëî â ãàçåòàõ

Ãëàçàìè äðóçåé

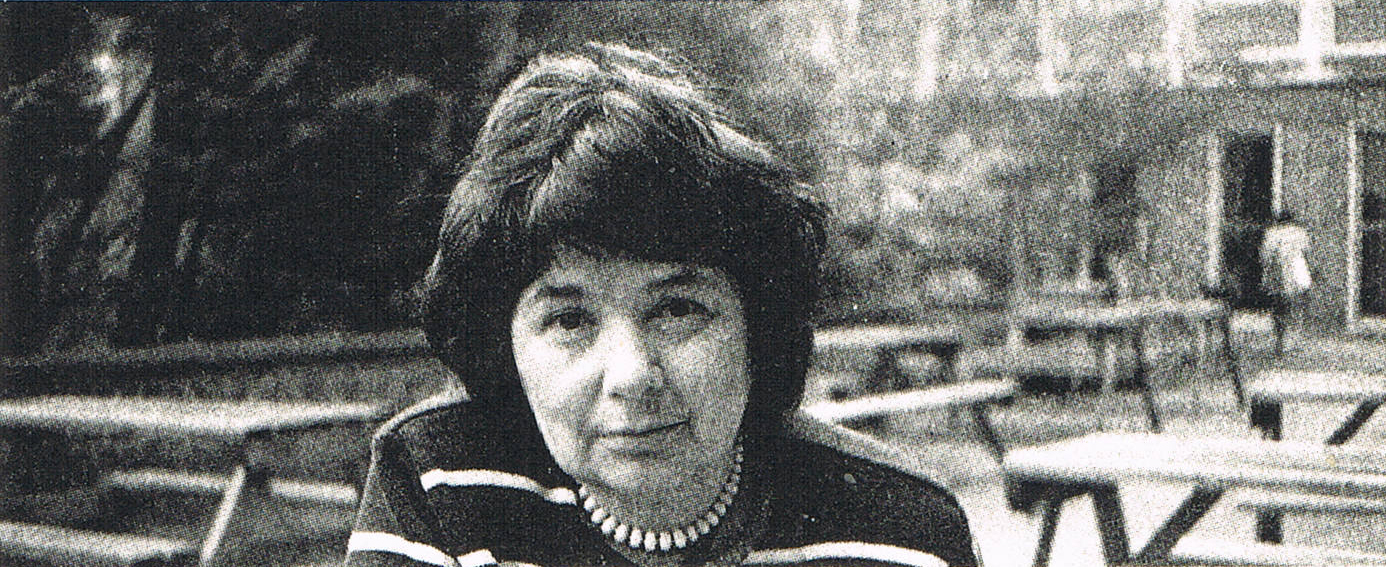

Over here Meet Renata Tkachenko from the Soviet Union Visitors to Britain air their views Ðóññêèé ïåðåâîä ÷èòàòü çäåñü. BBC English contents, volume 9, issue 59, pp. 22- 23, September 1991

Storytelling is a tradition in many countries. Using it to teach language is the passionate interest of Renata Tkachenko. She is Assistant Professor in the English Department of the University of Kharkov, Ukraine, URRS. Currently, Renata is a visiting fellow at the University of Bristol, in the southwest of England. Renata visited Britain in 1989 on her first trip to a non-communist country. Since then, she has been on two more short visits here.

Q. What brings you to Britain this time?

A. This time I have come at the kind invitation of the British Council who wanted me to take part in two conferences – the one here in Exeter (IATEFL) and one to follow in Oxford.

Q. Do you take your storytelling ideas to schools in the Soviet Union or do they come to you?

A. I take them to schools, to magazines, to universities, to colleges in Russia and I’m still a very representative body of one person! Because storytelling as a teaching activity is something that I think unfortunately still doesn’t exist in Russia. And I do hope – and I will be quite proud if I manage – to introduce it in our country.

Q. What are your stories about?

A. They are not my stories. They are the stories from English Literature which I collect. I look for wholesome, linguistic, psychological, compositional features and it so happens that I use mostly fairy tales. It all started with the Just So Stories for Little Children by Rudyard Kipling. You can imagine how difficult it was for me to get there stories, but some English people already knew what I was doing and they bought me books. Out of the many, many books I had, I chose the suitable stories. If Eric Carle exists, and I hope he does, I must thank him deeply for the story of The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The Elephant and the Bad Baby and Raymond Briggs and John Burningham’s charming story about Mr Gumpy’s Outing are stories written by British authors for British children. I found these just right for my purposes.

Q. Could you tell us what expectations you had of Britain when you first arrived?

A. I had a very, very difficult feeling of unreality about everything that was happening. I had spent all my life teaching English and doing something about England. I felt how you feel having never been to England. Coming from Russia where everything is on a very large scale, I expected everything to be much bigger. It was not disappointment, far from it, but it was, well, - Is this the Houses of Parliament? Is this all there is to it? Is Trafalgar Square so small? It was a question of scale, I had this sort of patronizing feeling “poor little country”. I immediately fell in love, not with London, but with your small places.

Q. Are there any aspects of the behavior of British people that have surprised you since you’ve been coming to Britain?

A. I wouldn’t say it surprised me. I met some English people when they came to Russia, that was one thing. I read a lot of books so in theory I knew everything about your famous “reserve”, you “sense of humour”. But it is one thing to listen to it, to hear about it – it is quite a different thing to be a part of it, an object of it. So not that I was surprised by my own reaction to that behaviour, and – I must say - it was not always a pleasant one and still is not. You may be very proud of being “reserved” people but “reserved” is an elegant word and what is represented by this word is not always easy to appreciate and enjoy.

Q. Could you give us some examples?

A. Yes, I have a very, very, very dear friend here, an English man, and he is also the husband of my dear friend. He is an absolutely charming person by all standards – Russian, English, European – with very sensitive manners. I met him in Moscow when my friend had just married him. He asked me then, during our first meeting, to tell him about anything he was doing wrong or not quite right by Russian standards. I promised and I immediately had a chance to keep my promise.

They had a room at Moscow University. I came there after two or three hours of work and – naturally, being Russian – I was hungry, and being myself – after seeing there very tempting goods and labels in their room, I was even hungrier because I wanted to try them. And I expected to be offered something to eat, as every Russian person would. My friend’s husband said to me “Renata would you like a cup of tea?” and I said “Yes please” and I looked with my mouth watering at two shelves with Marmite (I didn’t know what it meant) and biscuits. But what went on the table – was a cup and a saucer and a pot and that was that, and sugar. I had a cup of tea and he asked me if I would like another cup of tea and said “Yes, please”. I thought perhaps he had forgotten the rest. But there was another cup of tea and sugar and hot water – three times this was!

Q. Nothing to eat?

A. Absolutely! Then I said “Listen, you asked me to tell you about anything you do wrong in Russia. Take out your memo pad and a pencil and write it down. When you’re offering a Russian person a cup of tea you do not have to give this person soup – although you may, there is nothing wrong with it – but we would expect ham, sausage, cheese, herring, boiled potatoes, cake, sweets, jam, something to take home to the family if you have it.” And this poor creature looked at me. He turned grey, red, green, yellow, and he said “But that wouldn’t be a cup of tea”. “Never mind what that wouldn’t be, just put it on the table!”

Q. Are there any other aspects of our behaviour which have surprised you?

A. One of my latest, and least pleasant, experiences. When I came to Bristol, it was my third visit to England, so I thought I already knew everything. I came here on attachment with the School of Education, and my supervisor introduced me to the staff. I had a box of sweets and everybody was quite nice about it and we shared it. There were about 20 people there and I was absolutely excited and touched by the way they treated me. Nearly every person said “ Oh Renata, we must meet… must have a meal… must write an article… and you must come to our place”. I was very pleased. But I only had three months and I hoped I would have enough souvenirs to take to every household. That was a Monday and when I came on Tuesday I expected to be taken to at least two, perhaps three, of the 20 households. Nothing happened on Wednesday, on Friday and nothing happened for two months. I thought I must have done something very wrong. It was not a pleasant feeling; I was nearly depressed. By the end of my visit, when I knew people enough, I said “For God’s sake what happened, what have I done wrong?” They said “Nothing – what we said was just a social convention”. But you know, if it is a social convention you shouldn’t pronounce it with so much stress on “You must come, my wife would love", and must is must and when we say it with this sort of emphasis we usually mean it.

Q. What will you remember most about Britain?

A. The only unpleasant part will be that I don’t know whether I’ll ever see it again. That is a very unpleasant part, it starts immediately you set foot here. I will remember your countryside. I will remember the readiness of English people’s smile. I will remember the special colours of England, which are bright but not too demanding. I will remember how charming, although superficial, the people are – but still charming. I will remember how (unbelievably for me) the past, the very ancient past and the present are intertwined in England. That is something that is very typically English. What happened 2000 years ago is, in a way, still a part of your life.

Q. Is there something that you’d like to tell us that I haven’t asked you?

A. I would like to say and I mean it, that I am really very grateful to the people of the ELTEC scheme at the British Council, and to my fate, for giving me a chance to come here. I would also like to repay the hospitality and I will say it in English but meaning the Russian concept, “You must come and see us in Russia!”

visiting fellow - temporary member of a university or other academic institution

IATEFL - International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language. Their next annual conference will be held in Lille, France from 23-26 October 1992

representative body – normally refered to a group of people who act or make decisions on behalf of others. Here, Renata jokes about the fact that she is the only person doing it. She uses both meanings of body in a play on words

mouth watering – salvating

Marmite – a brand name for a popular vegetable spread in the UK

ELTEC – English Language Teaching Contacts Scheme. A British Counsel scheme which links English language teaching specialists from East and Centarl Europe with similar specialists in the UK